28 January 2020

Rare Omura’s whale spotted off Phuket Island

A rarely seen Omura whales has been spotted off Phuket Island close by Maithon Island, one of the few sightings globally of species that scientists know little about.

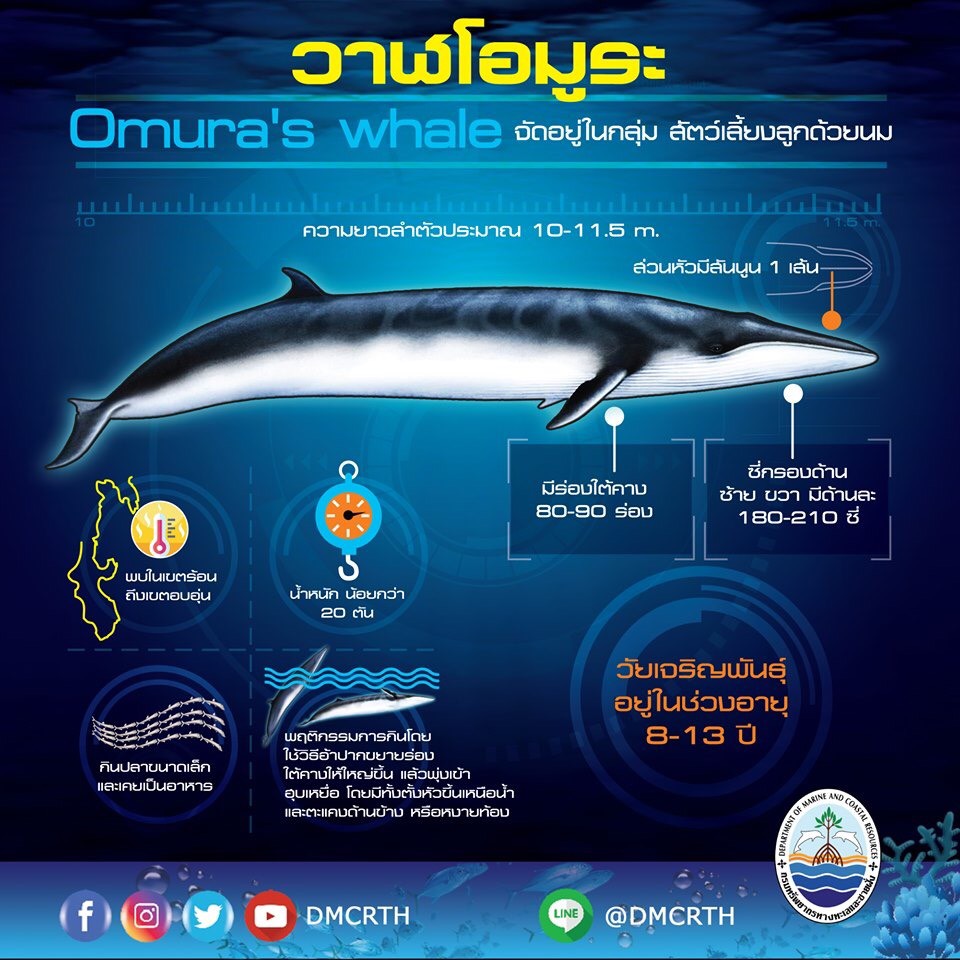

When the Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) was first described in 2003, it was known from only three locations: the southern Sea of Japan, and the vicinities of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Solomon Islands. Work over the following decade suggested a range limited to the eastern Indo-Pacific, but more recent discoveries in the western Indian Ocean and Atlantic Ocean suggested a more widespread range than previously thought. Here we use all available sources of information, including published papers, unpublished reports, and internet-based accounts, substantiated through genetic, morphological, photographic and acoustic documentation, to compile accounts of Omura’s whales globally. Reports increased precipitously since 2015 after publication of the first detailed external description of the species, reflecting the impact of the recently elevated awareness of the species. We report 161 accounts from 95 locales in the waters of 21 range states, and found that the species is widely distributed in primarily tropical and warm-temperate locations. Currently it is known from all ocean basins with the exception of the central and eastern Pacific. The majority of accounts remain in the eastern Indo-Pacific suggesting a potentially recent range expansion from this region. There is a strong tendency toward a coastal and neritic distribution, although there are also several pelagic records. A predominantly near-coastal distribution places Omura’s whale at risk from anthropogenic activities throughout its range, and its tropical distribution in often remote and poorly monitored areas makes adequately documenting and assessing threats challenging. We assess documented threats in light of the reported species’ range, and found threats from, at minimum, ship strikes, fisheries bycatch and entanglement, local directed hunting, petroleum exploration (seismic surveys), and coastal industrial development. Current evidence indicates that at least some populations are non-migratory with local, potentially restricted ranges. Furthermore, there is low genetic diversity documented throughout its global distribution. Given the species may be characterized by small local populations, it may be particularly vulnerable to impacts from existing regional anthropogenic threats. We recommend that focused work be conducted to locate and study local populations, assess potential population isolation, and determine conservation status and specific anthropogenic threats across the species’ range.

Introduction

The Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) was described as a new species distinct from and sister to the clade formed by the Bryde’s whales (B. edeni brydei and B. e. edeni) and sei whale (B. borealis), through mitochondrial DNA sequencing, skeletal morphology and a limited description of external characteristics (Wada et al., 2003). A species-level status was first proposed by Wada and Numachi (1991) and Yoshida and Kato (1999), and the phylogenetic relationship supported by work using additional markers (Sasaki et al., 2006; Rosel and Wilcox, 2014). Estimated time of lineage divergence was initially 17 million years (Sasaki et al., 2006), but more recent work suggests a more recent divergence at 7–9 million years (Marx and Fordyce, 2015; Slater et al., 2017). The initial species description was based on a 1998 stranding in the Sea of Japan (the holotype specimen, which included the complete skeleton and baleen plates) along with tissues, morphological data and descriptions of eight specimens taken in the late 1970s by Japanese research whaling vessels near the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Solomon Islands (Wada et al., 2003). Prior to the collection of the holotype specimen, the eight whaling specimens had been attributed to Bryde’s whale (B. edeni) but recognized as distinct due to their diminutive size, divergent allozyme profiles and partial mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes; these were referred to as “small” or “small-form” Bryde’s whales (Ohsumi, 1980; Wada and Numachi, 1991; Yoshida and Kato, 1999). Relatively concurrent with work on these aforementioned specimens, indigenous whaling specimens from the Bohol Sea, Philippines, were noted to have atypically small skulls for B. edeni and divergent mtDNA cytochrome b sequences (Perrin et al., 1996; LeDuc and Dizon, 2002) and were later identified as belonging to B. omurai (Sasaki et al., 2006; Yamada et al., 2008). Between 2003 and 2012, several specimens were identified primarily through examination of skulls throughout the Southeast Asian region (Yamada et al., 2006a, 2008; Yamada, 2009), which was possible due to the detailed description of skull morphology available from Wada et al. (2003). Through this work, the range of the species was thought to be restricted to the eastern Indo-Pacific region, more specifically the tropical eastern Indian Ocean and western Pacific Ocean.

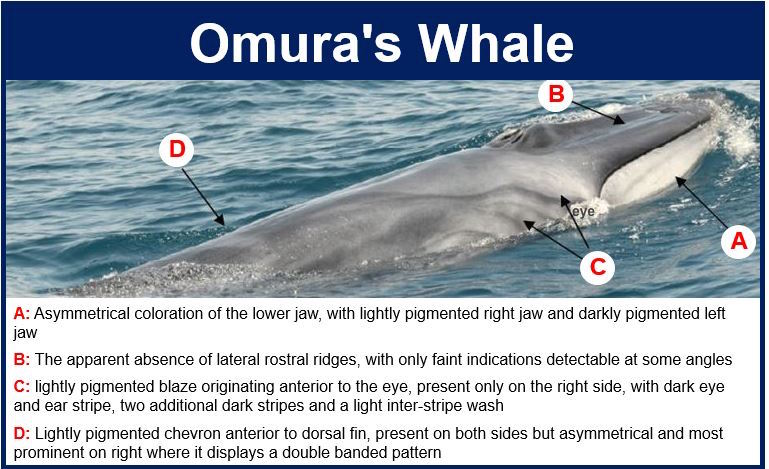

In 2013 a population of Omura’s whales tractable for long-term monitoring was discovered off the northwest coast of Madagascar, extending the range into the western Indian Ocean (Cerchio et al., 2015). Following shortly on this report, a stranding off the coast of Mauritania was genetically identified extending the range much further into the tropical eastern North Atlantic Ocean (Jung et al., 2015). Prior to 2015 there was only a limited description of the species drawing similarities to the asymmetrical pigmentation of fin whales, based on the Sea of Japan stranding and Cocos (Keeling) Islands and Solomon Islands whaling specimens (Wada et al., 2003); however, no good photographic evidence or any documentation of free-ranging live animals with confirmed species attribution were available. Through the use of detailed surface and underwater still photographs and video, combined with genetic verification (mtDNA) of simultaneously collected skin biopsies, Cerchio et al. (2015) described in detail the external physical appearance and pigmentation patterns. Thereafter, numerous reports have been made in peer-reviewed scientific literature, gray literature and internet-based accounts, primarily in shallow coastal waters and expanding the range to most ocean basins from the western South Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean, the northwest Pacific Ocean and Oceania (Cerchio and Yamada, 2018).

Here we summarize all records that we could find relating to the global distribution of Omura’s whales, drawing upon all available sources of information, in an effort to better establish the known range and begin to assess range-wide threats to the species, especially at the regional level.